From fangs to facts: Debunking Rattlesnake Myths and Learning the Art of Rattlesnake Relocation

Last year, my son and I completed a rattlesnake relocation training class at the Phoenix Herpetological Sanctuary—a place where the snakes are real, the training is hands-on, and the experience is unforgettable. Under professional supervision, we each had a turn safely relocating a live rattlesnake, which definitely made me rethink a few things I thought I knew about these iconic reptiles. A few months later, we joined a rattlesnake research night hike to experience fieldwork with the pros.

Turns out, a lot of what we hear about rattlesnakes falls somewhere between folklore and flat-out fiction. So, before you assume every rattlesnake is an 8-foot monster with a short temper and Olympic-level striking distance, let’s clear up a few myths.

I’ll hold off on the snake photos until the end of this post, so you can digest the myths first—without needing to sleep with the lights on. You’re welcome, Mom.

Table of Contents

🐍 Myth #1: Rattlesnakes are aggressive and will chase you down

Reality: Rattlesnakes are not the Jason Bournes of the desert. They don’t chase people—they see us as threats and want nothing to do with us. In fact, if it looks like a snake is coming toward you, it’s probably just trying to take the quickest escape route, and you happen to be in the way. That’s not aggression—that’s panic. More often than not, they’ll simply go around your feet and head for the nearest bushes.

🐍 Myth #2: Rattlesnakes always give a warning rattle before striking

Reality: Not even close. Most rattlesnakes rely on camouflage, not rattles, to stay out of trouble. In a study conducted by the Venom Manager at the Phoenix Herpetological Sanctuary, 95% of the snakes didn’t rattle until he attempted to pick them up with tongs. The rattle isn’t a threat—it’s a last resort, signaling that the snake is scared. A variety of animals, including roadrunners, hawks, owls, bobcats, mountain lions, coyotes, and kingsnakes, can kill and eat rattlesnakes. So, rather than announcing their presence, rattlesnakes prefer to stay undetected and avoid drawing attention.

🐍 Myth #3: Baby rattlesnakes are more dangerous than adults

Reality: Research shows that adult rattlesnakes actually pack a bigger punch. The venom yield of adult rattlesnakes is larger, and the effects of their bites are typically more severe.

🐍 Myth #4: If you step on a rattlesnake, it’ll bite you

Reality: You’d think so. But in an eye-opening (and slightly terrifying) experiment, Cale (Venom Manager at Phoenix Herpetological Sanctuary) stepped on 175 rattlesnakes using a fake leg. Only 6 of them struck his boot (that’s just 3%), and 3 coiled defensively. The rest? They either stayed frozen or tried to slip away. Of course, this doesn’t mean you should start stomping around blindly. Just know that most bites happen when people reach into bushes or rock crevices without looking first.

🐍 Myth #5: Rattlesnakes can grow to 8–12 feet long

Reality: Sorry, but that rattler your uncle saw last summer that “must’ve been 10 feet long”? It wasn’t. The longest snake recorded by the Phoenix Herpetological Sanctuary since 2001 was 4 feet 1 inch. Most are closer to 3 feet. Similarly, most adult rattlers in New Mexico are no longer than 3–4 feet. And if you see one stretched out, it’s likely moving—usually slowly. Give it a couple of minutes to cross the road. No need to speed up the process with your tires.

🐍 Myth #6: Rattlesnakes can strike their full body length

Reality: They can’t. A rattlesnake can typically strike about 1/3 of its body length. So, a 3-foot snake has about a 1-foot striking range. That’s still impressive—but a far cry from the snake-catapult scenario some people imagine.

🐍 Myth #7: Hundreds of people die from rattlesnake bites every year

Reality: Fatalities from rattlesnake bites are extremely rare. In Arizona, local Poison Control data suggests that fewer than 1% of bites result in death. Still, that doesn’t mean you want to test your luck—if you’re bitten, get medical attention immediately.

Fun Rattlesnake Trivia (Because You Never Know When This Will Win You a Bar Bet)

- They don’t want to waste venom on you. Rattlesnakes can actually deliver a “dry bite” when they don’t want to waste precious venom. Why? Because venom takes time and energy to produce—and it’s meant for dinner, not self-defense.

- The rattle is made of keratin—the same stuff as your fingernails. Every time a rattlesnake sheds its skin, a new rattle segment is added. But no, you can’t tell a snake’s age by counting the rattles—they break off over time, and some snakes shed multiple times a year.

- Rattlesnakes give live birth. Unlike many snakes that lay eggs, rattlesnakes are ovoviviparous. That means the eggs hatch inside the mother, and she gives birth to live, cute young. OK, maybe not “cute” cute.

- They’re pretty chill—by reptile standards. Rattlesnakes spend about 85–90% of their lives lying still. They’re the introverts of the reptile world, perfectly content hiding in rocks, soaking up sun, and avoiding drama.

- They’ve been around for a long time. Fossil records show that rattlesnakes have existed for at least 8 to 10 million years. They’ve been perfecting the art of desert survival a lot longer than we have.

- They can swim. Yes, you read that right. Rattlesnakes can cross rivers, lakes, or even your backyard pool if they have to. So, if you see one doing the backstroke—don’t panic. Just give it space.

- Rattlesnakes will always win a staring contest, but they won’t hear you swear when you lose. After all, rattlesnakes have no eyelids (so they can’t blink) and no ears. However, they do have excellent eyesight, so they’ll see you lose the contest. They just won’t be able to hear your frustrated muttering. But don’t worry—they’ll feel the vibrations as you walk away.

What to Do If You Encounter a Rattlesnake at Home or on the Trail

Encountering a rattlesnake—whether you’re hiking in the wild or simply working in your yard—can be a startling experience. While these snakes are often misunderstood, it’s important to approach any encounter with calm and respect. Here’s what you need to know and do to stay safe.

- Stay Calm and Keep Your Distance. The most important thing to remember when you encounter a rattlesnake is to stay calm. Rattlesnakes are more likely to strike if they feel threatened or cornered, so it’s crucial to avoid panicking. Give the snake space and do not attempt to touch or handle it. If you’re on the trail, take a slow step back and move away, maintaining a safe distance of at least 6 feet. If you’re at home, stay clear and keep pets or children away from the snake.

- Do Not Attempt to Handle the Snake. Rattlesnakes should only be handled by trained professionals. Whether you’re at home or on the trail, do not attempt to move the snake. If you’re on the trail, keep walking slowly and quietly around it, giving it plenty of room to retreat. At home, contact local wildlife control or a rattlesnake relocation expert. Remember, rattlesnakes are protected wildlife in many areas, and it’s often illegal to harm them.

- Using a Hose to Encourage Movement. If a rattlesnake is in a location where you need it to move (e.g., your yard or driveway), spraying it with a hose can be a non-invasive way to encourage it to leave the area. The vibration and water pressure from the hose are generally enough to startle the snake into slithering away. While spraying a rattlesnake with a hose can be effective, it’s important to remain calm and make sure the snake has an easy escape route. If you’re unsure about how to handle the situation or if the snake is too close for comfort, it’s always best to contact a local wildlife control or rattlesnake expert.

- Important Tips:

- Use gentle pressure and aim the water toward the ground in front of the snake. Avoid soaking it directly, as this could cause distress.

- Don’t use a strong jet of water or try to force the snake off. The goal is to encourage the snake to retreat, not to provoke it into defensive behavior.

- Always stay a safe distance from the snake while spraying, as rattlesnakes may still react defensively, especially if they feel cornered.

- This method works best if the snake is near the edge of your property or near an open area where it can safely move away. I had success with this approach when a prairie rattlesnake decided to greet me at the front entrance of my house. Nothing like a surprise guest—especially one that doesn’t RSVP. Luckily, a gentle spray of water from a hose and a little patience sent it on its way.

- Important Tips:

- What to Do if Bitten. Although rattlesnake bites are rare and deaths are even rarer, it’s still essential to be prepared in case of an emergency. If you or someone else is bitten:

- Stay calm and call emergency services immediately.

- Keep the affected limb immobilized at or slightly below heart level to slow the spread of venom.

- Do not attempt to suck out the venom or apply ice.

- Avoid drinking alcohol or caffeine, as they can speed up the spread of venom.

- Get to the hospital as quickly as possible—antivenom is the most effective treatment for rattlesnake bites.

- Prevention Tips. The best way to handle a rattlesnake encounter is to avoid one altogether. Here are some simple prevention tips for your home and while on the trail:

- Keep your yard tidy by trimming tall grass and removing debris where snakes could hide.

- Seal gaps around your home’s foundation, doors, and windows to prevent snakes from entering.

- Wear protective gear when hiking, such as thick boots and gaiters, and be cautious when stepping into tall grass or rocky areas.

- Watch your step and stay on established trails while hiking. Look ahead and watch the ground around you, especially in the early morning and evening when snakes are most active.

Rattlesnakes are an important part of the ecosystem and, with a little knowledge and respect, you can safely coexist with them. By staying calm, keeping your distance, and knowing the proper steps to take, you can enjoy your outdoor adventures—and your backyard—without incident.

Preventing Your Pets from Getting Bitten by Rattlesnakes

If you live in an area with rattlesnakes, keeping your pets safe should be a top priority. Rattlesnake bites can be dangerous, even fatal, to dogs and other pets, so taking steps to minimize the risk is essential.

- Keep Your Yard Tidy. Rattlesnakes are often drawn to places where they can find shelter, such as tall grass, piles of debris, or rock piles. Keep your yard clear of clutter, and regularly mow tall grass to remove hiding spots. You can also trim back shrubs and bushes that could provide cover for snakes. A clean yard is a less inviting place for them to settle in.

- Install Rattlesnake Fencing. If you live in an area where rattlesnakes are common, you can install rattlesnake-proof fencing around your property. This fencing is designed to be high enough and tightly spaced to prevent snakes from slithering under or over it. It can also be angled outward at the base to discourage climbing. This is an effective way to keep snakes out, especially around areas where your pets like to roam.

- Train Your Dog to Stay Away from Snakes. Training your dog to avoid snakes can be one of the most effective ways to prevent snake bites. Some pet owners opt for rattlesnake aversion training—a specialized course that teaches dogs to recognize and avoid snakes. During these courses, dogs are exposed to the scent and sound of rattlesnakes in a controlled environment, so they learn to stay away when they encounter them in the wild. If you’re in an area with frequent snake sightings, this could save your pet’s life.

- Be Extra Cautious on Walks or Hikes. When walking your dog, especially in rattlesnake-prone areas like deserts or mountain trails, always keep your dog on a short leash. Snakes tend to hide in tall grass or underbrush, so leashing your dog will give you more control over where they go. Watch for signs of snakes, and if you see one, calmly move your dog away from the area. Always stay alert to your surroundings, especially in the warmer months when snakes are more active.

- Vaccination. If you live in an area with a high rattlesnake population, consider talking to your vet about a rattlesnake vaccine. While not foolproof, this vaccine can help reduce the severity of the bite if your dog is bitten. It stimulates an immune response to neutralize the venom, giving you more time to get your pet to a vet for treatment. Keep in mind that the vaccine is not a substitute for antivenom, and you’ll still need to seek immediate veterinary care.

- What to Do If Your Pet Is Bitten. If your pet is bitten by a rattlesnake:

- Stay calm—panicking will only make the situation worse.

- Get your pet to a vet immediately—rattlesnake venom can act quickly, and the sooner treatment is started, the better the chances of recovery.

- Keep your pet as still and calm as possible to slow the spread of venom.

- Don’t try to administer antivenom yourself. While it might be tempting to administer rattlesnake antivenom yourself in an emergency, it’s important to understand that antivenom should only be administered by a trained medical professional. This applies to both humans and pets. Administering antivenom incorrectly can lead to allergic reactions, serum sickness, or improper dosing, which can be life-threatening.

If bitten by a rattlesnake, whether it’s you or your pet, the best course of action is to get to a hospital or veterinary clinic immediately. Never attempt to handle antivenom yourself unless you’re a trained professional. In a medical setting, professionals can safely administer antivenom, monitor the patient’s response, and provide the necessary treatment for recovery. Time is critical, so always seek professional care right away. As our instructor shared, an emergency room physician once told him, “Time is tissue”—the longer you wait for treatment, the more damage is done.

Safely Relocating a Rattlesnake (AKA: Don’t Try This Unless You’re Trained)

If you ever find yourself needing to relocate a rattlesnake, here’s the key takeaway: don’t do it unless you know what you’re doing. Snake handling is not a DIY activity. That said, here’s a brief overview of how trained professionals at Phoenix Herpetological Sanctuary do it:

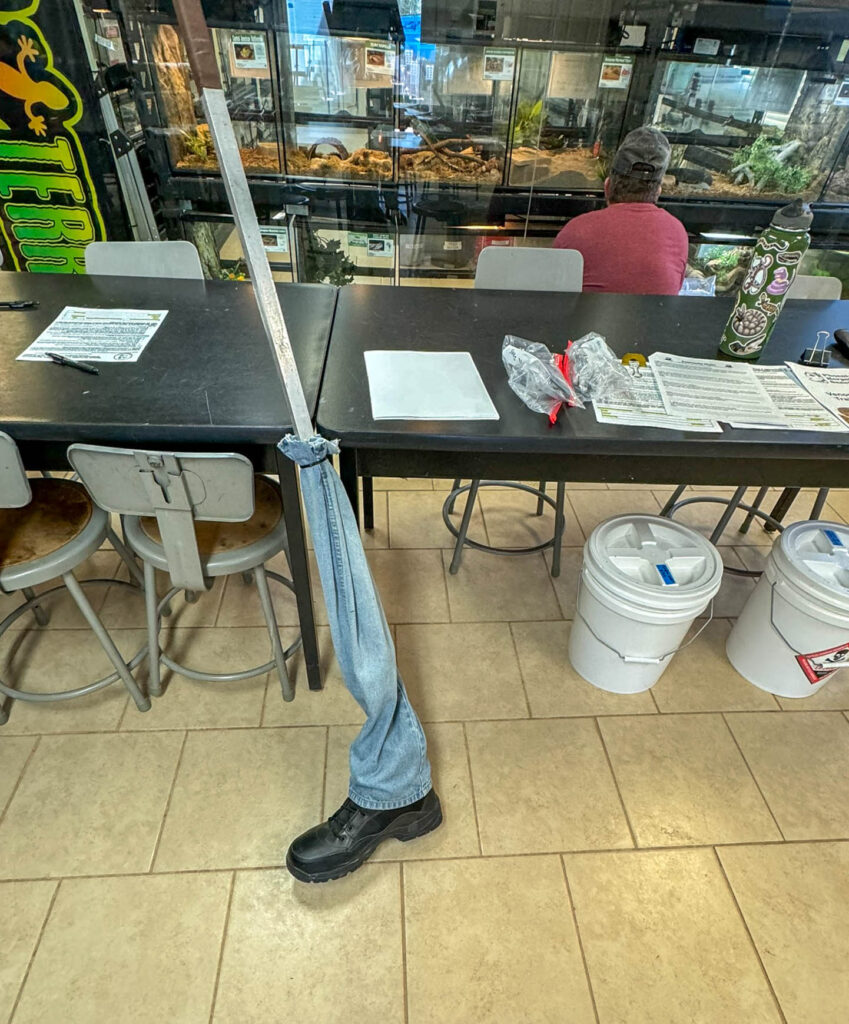

- Wear Proper Gear: Boots, long pants, snake gaiters, gloves, and eye protection, depending on the situation.

- Use the Right Tools: We used 40-inch standard tongs from Midwest Tongs (www.tongs.com) and a secure bucket with a locking lid. Always use a “pistol grip” on the tongs and never place your second hand lower on the tongs.

- Prepare the Bucket: Remove the lid and hold it beneath the tongs. The lid serves as support and as a shield while you handle the snake.

- Identify the Species (if possible): Safely identify the species from a distance before attempting to catch it, so you know what you’re dealing with.

- Approach Calmly: Avoid sudden movements or attempts to “herd” the snake.

- Grabbing the Snake: With the tongs in one hand and the lid in the other, gently grab the rattlesnake IN THE MIDDLE OF ITS BODY (halfway down). Never grab it near the head or tail. The lid supports the tongs and the snake. Maintain a firm but gentle grip—if the snake is difficult to handle, place it back on the ground until it’s more manageable.

- Guiding the Snake into the Bucket: Take your time and be patient. Gently guide the snake into the bucket.

- Securing the Snake: Do not release the snake until the tongs are fully at the bottom of the bucket. Check to ensure the snake’s head is at the bottom before releasing. Slowly release the tongs and GENTLY tap the snake on the head with the tongs to encourage it to stay in the bucket for a few extra seconds, giving you time to secure the lid.

- Relocating the Snake: Choose a release site with natural habitat—plenty of cover, food, and shelter—far from human activity. Make sure the site matches the snake’s preferred environment in terms of elevation and temperature, and always seek permission from landowners or local authorities.

- Releasing the Snake: To release the snake, unscrew the lid and lift it off all at once. Avoid peeking inside. Grab the snake in the middle of its body with the tongs (using the lid as support). Gently place the snake in front of a bush, rock, or other natural shelter, and release it into the wild.

- Don’t take shortcuts and always stick to the protocol!

During our Rattlesnake Relocation Training class at the Phoenix Herpetological Sanctuary, we practiced all of these steps under close supervision—with live rattlesnakes. While the nerves were real, so was the value of learning how to handle these creatures with respect rather than fear. There’s truly no substitute for taking a class like this, where you can gain hands-on experience with a professional guiding you.

Alright, it’s time for the snake photos and videos! Proceed at your own risk.

Rattlesnakes of New Mexico: Local Legends and Cold-Blooded Celebrities

New Mexico is home to eleven confirmed species of rattlesnakes, if you include two visually distinct subspecies of the Rock Rattlesnake. Each species occupies its own ecological niche—and has its own unique ‘personality,’ if you’ll indulge a bit of light anthropomorphizing. If you plan to hike, camp, or wander off-trail in New Mexico, it helps to be familiar with the rattlesnakes that call the state home.

Western Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox)

The Western Diamondback Rattlesnake is the most iconic and widespread rattlesnake in the Southwest. With its bold, black-and-white banded tail, this species can be found throughout much of New Mexico, typically below 7,500 feet. If you picture a stereotypical rattlesnake, this is the one.

Prairie Rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis)

More common in northern and eastern New Mexico (though it’s been found in nearly every county in the state), the Prairie Rattlesnake is often found in grasslands and high desert areas. They’re known to take refuge in prairie dog tunnels and other preexisting shelters, especially during extreme temperatures. While they’re considered slightly more mellow than their Diamondback cousins, don’t be fooled—they’re still venomous and will defend themselves if threatened.

Rock Rattlesnake (Crotalus lepidus)

A highly cryptic species found in mountainous, rocky terrain—especially in the Gila Wilderness, Black Range, and Organ Mountains. They’re experts in camouflage, often matching the color of the local granite or limestone perfectly. In New Mexico, this species is represented by two distinct subspecies:

- Mottled Rock Rattlesnake (C. l. lepidus). A rare sight in the rugged, mountainous terrain of southern New Mexico, the Mottled Rock Rattlesnake’s irregular, blended blotching and muted, mottled appearance make it perfectly suited to blend into its rocky surroundings.

- Banded Rock Rattlesnake (C. l. klauberi). More common in the southwestern mountains near New Mexico’s “Bootheel,” Banded Rock Rattlesnakes typically display higher contrast and more defined dark bands across a paler background, compared to their mottled relatives. Think of them as the more sharply dressed cousin of the Mottled Rock Rattlesnake.

Black-tailed Rattlesnake

Several years ago, the Black-tailed Rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus) was split into two distinct species: the Western Black-tailed Rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus molossus), also known as the Northern Black-tailed Rattlesnake, and the Eastern Black-tailed Rattlesnake (Crotalus ornatus). New Mexico is home to both species. Often mistaken for a nonvenomous snake due to its sleek, greenish-yellow body and calm demeanor, both Black-tailed Rattlesnake species are easily identified by their signature black tail and rattle. While there are subtle differences between the two, a simple rule of thumb is that the Western is found west of the Continental Divide, and the Eastern to the east, though some overlap does occur.

- Western Black-tailed Rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus molossus). A generalist, it inhabits southwestern New Mexico’s foothills and rocky canyons up to elevations of 8,000 feet. Despite its peaceful nature, it’s always wise to respect its space. To add to the confusion, the western black-tailed rattlesnake is also known as the Northern Black-tailed Rattlesnake.

- Eastern Black-tailed Rattlesnake (Crotalus ornatus): Found primarily in the foothills and canyons of eastern New Mexico, the Eastern Black-tailed Rattlesnake is a stout, medium-sized rattlesnake with striking black bands at the tail. It is one of the most common rattlers in the Organ Mountains and the Sandia foothills, though it typically avoids urban environments. Preferring rocky outcrops and desert grasslands, it’s commonly found at elevations up to 7,000 feet. While generally calm and elusive, it’s always a good idea to give this rattlesnake plenty of space to avoid startling it.

Northern Mojave Rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus scutulatus)

Often mistaken for Western Diamondbacks, the Mojave Rattlesnake is a highly venomous species found primarily in the extreme southwestern part of New Mexico, near the borders of Arizona and Mexico. Known as one of the most toxic rattlesnakes, its venom is both neurotoxic (affecting the nervous system and potentially causing paralysis in its prey) and hemotoxic (affecting blood and tissues, leading to internal bleeding and disrupting blood clotting). While the Mojave Rattlesnake is generally reclusive and prefers to avoid human contact, it can become defensive when threatened, striking with impressive speed and accuracy.

Tiger Rattlesnake (Crotalus tigris)

The Tiger Rattlesnake is a rare find, confined to the extreme southwestern corner of New Mexico—and it’s one you’ll definitely want to avoid. Known as the most venomous rattlesnake in the world by toxicity, its venom is relatively simple yet incredibly potent. Highly neurotoxic, it rapidly paralyzes and kills its prey, making it a snake best admired from a safe distance.

Arizona Black Rattlesnake (Crotalus cerberus)

You’re unlikely to encounter the Arizona Black Rattlesnake in New Mexico unless you’re in the rugged mountain ranges of southwest part of the state, particularly in the Mogollon and San Francisco mountains, where it resides at elevations between 3,900 and 9,000 feet. Adapted to the cool, rocky environments, this elusive species thrives in the higher, more isolated regions of the state.

New Mexico Ridge-nosed Rattlesnake (Crotalus willardi obscurus)

New Mexico’s rarest rattlesnake, and both a federally listed threatened species and a state-listed endangered species, the New Mexico Ridge-nosed Rattlesnake is found only in the mountains of the far southwestern “Bootheel.” Small, secretive, and distinguished by its unique ridged snout, this elusive snake is a bucket-list sighting for herpetologists and conservationists alike. As a protected species, it should not be harassed or collected.

Western Massasauga (Sistrurus tergeminus edwardsi)

The Western Massasauga (also known as the Desert Massasauga or Edward’s Massasauga) is a small, venomous pit viper that’s part of the rattlesnake family. The name “Massasauga” comes from the Ojibwe word meaning “great river” or “great snake,” referring to its habitat near bodies of water. Found primarily in the semidesert grasslands and rolling hills of southern and central New Mexico at elevations ranging from 3,500 to 4,600 feet, this rattlesnake species prefers to stay hidden during the day and becomes more active in the evening and early morning hours.

Rattlesnake Research Night Hike

After completing our rattlesnake relocation training earlier in the year, my son and I returned to the Phoenix Herpetological Sanctuary for a night hike focused on rattlesnake research. We suited up with snake gaiters, headlamps, and plenty of caution—because style points don’t count when you’re trekking through rattlesnake country after dark. Once the headlamps came out and our group hit the trail, it was time to trade concrete sidewalks for sandy paths and see who else was out there tonight.

Finding snakes in the wild, even with radio transmitters attached to a few individuals, proved challenging. Many were so well-camouflaged that even trained eyes walked right past them. At one point, a large scorpion sat squarely in the middle of the trail, invisible until a lucky headlamp beam revealed it. Thanks to the transmitters (and a lot of careful searching), we spotted around five Western Diamondback Rattlesnakes over the course of 90 minutes.

Here’s a series of photos that offer a glimpse into the experience.

Final Thoughts

Rattlesnakes aren’t out to get us. They’re not monsters, and they’re not villains. They’re just another part of the desert’s delicate balance—misunderstood, often maligned, and honestly, kind of fascinating once you get to know them.

If you’re ever in the Phoenix area and interested in learning more, I highly recommend checking out the rattlesnake training courses at the Phoenix Herpetological Sanctuary. You’ll walk away with a healthy respect for rattlesnakes, a better understanding of how they behave, and maybe even the confidence to relocate one—if you’re trained and ready.

Until then, keep your hands out of bushes, your myths in check, and your boots where you can see the ground.

Thought for the Week

This week’s quote comes from Friedrich Nietzsche, the German philosopher renowned for his bold, sometimes controversial ideas on life, growth, and human nature. Nietzsche believed in the necessity of personal transformation—not just for the individual, but for society as a whole. His philosophy often centered on overcoming obstacles and becoming something greater, much like the process of shedding old habits and beliefs to make way for new growth.

This week’s quote echoes this central theme. Just as a snake must shed its skin to survive and grow, Nietzsche suggests that humans must also release outdated ideas, identities, and attachments to truly thrive. The “death” he refers to is figurative—not literal—representing the stagnation that occurs when we fail to adapt, evolve, or challenge ourselves. Nietzsche wasn’t merely talking about snakes; he was speaking to the heart of human potential and the necessity of change.

So, this week, consider what needs to be shed in your own life. What outdated beliefs or patterns are holding you back from growth? Just as the snake must shed its skin to continue moving forward, we too must be willing to cast off limiting ideas in order to evolve. It’s a powerful reminder that growth, whether physical or philosophical, often requires transformation—and sometimes, a little discomfort.

“The snake which cannot cast its skin has to die. As well the minds which are prevented from changing their opinions; they cease to be mind.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche

Thanks for reading and happy travels!

Mark (The New Mexico Travel Guy)

Mark Aspelin, The New Mexico Travel Guy (www.newmexicotravelguy.com), is a travel writer and author of two books who has enjoyed a wide variety of adventures in his travels to over 100 countries and all 50 U.S. States. His current project involves visiting EVERY town in his home state of New Mexico (there are 582 towns on his list) and writing a story about each one. He’s on track to finish the project by his early-mid 100s. When not traveling, Mark lives as a recluse in the mountains outside of Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Leave a reply